In August 2018, thousands of members and representatives helped The Royal British Legion recreate the 1928 Battlefields Pilgrimage to mark the centenary of the launch of the ‘Hundred Days Offensive’.

A decade after the end of WW1, the British Legion organised for 11,000 veterans and war widows to visit the battlefields of the Somme and Ypres, before marching to the Menin Gate in Ypres on 8 August 1928.

In 2018, exactly 90 years on, the Great Pilgrimage 90 saw 1,150 branches, and thousands of members and representatives from the UK and abroad, help The Royal British Legion recreate their original pilgrimage.

Here at Leger Holidays, we are immensely proud to have been a part of this magnificent event. It was an absolute honour to have helped make this happen, and not only are we thankful to our many coach crews and Battlefield Guides who took part, but also each and every person who joined us and make this one of our most memorable moments of Leger history.

To commemorate the event, we have put together a moving collection of accounts from our Battlefield Guides who joined us for GP90. Read all about their fascinating stories, below.

Terry Whenham

It all started for me one day in 2001. I was in a military cemetery on the Somme battlefield staring down at my own family name on a headstone. On a cold, blowy April day I then found myself walking, as he did, across the same field 85 years after he was mortally wounded. He was my Great Uncle Henry who had died in August 1916, leaving behind a fiancée called Dolly.

Fast forward 17 years ago and I found myself on the same Somme battlefield guiding 40 enthusiastic British Legion members as part of their GP90 commemorations. Although I had been organising and leading battlefield tours for many years, it was the first time I had been asked to guide such a large group and, being part of the Leger Group, I was determined to make the tour a success, although I was a bit apprehensive!

As we toured such iconic places such as Vimy Ridge, Delville Wood, Hill 60 and Arras, it was an exhilarating experience. I was able to share my passion and knowledge with everyone on board, many of who were veterans from recent conflicts. The impact of the stories I told the passengers was immense, and everyone shared in the shock, amazement and grief of the Victoria Cross winners, boy soldiers, shot at dawn men and ordinary soldiers who carried out incredibly brave actions.

I told the story of how 3 Victoria Crosses were won on Hill 60, in the midst of a gas attack. The group stood at the graves of 2 soldiers in Arras, buried next to each other, who were “shot at dawn”. On the Arras Memorial, they discovered Walter Tull, a professional footballer from my home town who became an officer, despite suffering dreadful racism. At the Thiepval Memorial, they learned about Private John Dewsbury who wrote a beautiful letter to his mother as he lay mortally wounded in a shell hole. I told these stories with tears in my eyes. It was an experience that nobody who was there on those very hot August days will ever forget. Or me either.

Ste Lingard

Being part of the Royal British Legion’s “Great Pilgrimage 90” last August was a highlight of all my time on the battlefields. I joined more than two thousand men and women from across the United Kingdom in marking the 90th anniversary of the original “Great Pilgrimage” when 10,000 veterans and relatives made the same trip, just 10 years after the war.

On Monday we visited Ypres (now Ieper) and the surrounding area, including Hill 60, Messines, Zonnebeke and Tyne Cot Cemetery – the final resting place for almost 12,000 British and Commonwealth servicemen.

We spent Tuesday on the Somme and at Arras, visiting Delville Wood (where we found a large howitzer shell sticking out of the ground – and left it well alone), Thiepval, Vimy Ridge and the Arras Memorial.

Wednesday was the focal point of the pilgrimage. The veterans paraded through Ypres: 1,200 standard bearers and 1,200 wreath layers, led by the Royal Marines Band. All took part in a service beneath the Menin Gate, remembering the sacrifices made throughout the war and the anniversary of the Battle of Amiens in 1918, which marked the start of the greatest series of victories in the British Army’s history. It was an impressive and moving day.

Towards the end of the trip, one of the group asked me if I had enjoyed it. Yes, I had, and listening to the veterans was the best part: the Guardsman who had been part of the Guard at King George VI’s funeral and Elizabeth’s coronation; the 79 year old physical training instructor – still a fine runner – who had served in the Royal Marines, Lancashire Fusiliers and Royal Air Force; and the quiet gentleman who kept himself to himself, but paraded in the sand beret and winged dagger badge of the SAS, and turned out have been a Colonel in that most elite of regiments – veterans stood as he passed, and in the pub after the parade, beer appeared in front of him as if by magic.

As a freelance historian and guide, I was fortunate to be working with Leger. They handled the complex logistics involved in such a large operation with great professionalism and provided support to those who needed it at all hours of the day. You can relax knowing that you are in safe hands.

I hope you find your pilgrimage rewarding and enjoyable.

Phil Arkinstall

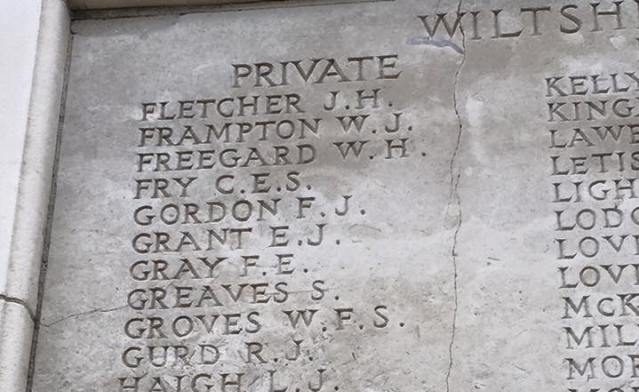

As a history teacher, I have led tours to the battlefield before for my school, but when I was given the job as guide for Coach 928 for GP90 I was over the moon. This was my first tour working for Leger and I couldn’t have been more thrilled and proud. My role was to lead members from the British Legion to historic sites around Ypres and the Somme before their parade. My favourite activity was taking a series of photo cards of soldiers who had come from Wiltshire and whose bodies were never found; their names being on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing. My group loved the idea and were keen to get involved. At the end, we had a photo taken with all members holding a soldier – for so many it was powerful to see the faces of those who don’t have a known grave and helps to represent a small number of the scores of men who gave their lives.

For me though, it was parade day that I was most looking forward to. The sheer sense of determination from the Legion members who either carried a wreath or held the standard was very moving. For each person who took part they were not just representing their branch, but their county, the nation as a whole and the memory of the men and women who gave their lives for the freedoms we observe today. That is the reason so many took part and the reason why I wanted to be part of this anniversary. It will be one of the proudest moments of all our lives. The weight of responsibility each person must have felt was equalled with their own sense of pride and can be seen in photographs and on the televised screens. A special mention must go to Bill Dobson, the standard bearer from Edington was one of the oldest members of the group and his sense of duty and regard to his standard saw that he held it throughout the entire march. It is this level of respect and utter sense of duty that I will take away from GP90 and I hope that I get to pass this on to all the pupils that I teach at my school. The legacy of this event is that in another hundred years, younger generations are still paying their respects for the generation that sacrificed it all

Shaun Coldicutt

From Sunday 5th August – Thursday 9th August 2018 I had the pleasure of taking and guiding a group of 47 Royal British Legion members on a tour of the Western Front for the “Great Pilgrimage”; commemorating both ninety years since 11,000 Royal British Legion members (Veterans, widows and officials) toured the battlefields in 1928 culminating in a parade in Ypres through the Menin Gate and to overall, commemorate those involved in the First World War.

Not only were the footsteps of 11,000 strong some ninety years previous retraced through the battlefields of France and Flanders, but this trip also witnessed new legacies, stronger bonds forged and lasting memories for all involved.

As one of the sixty unprecedented battlefield guides to accompany the trip, it was our job to ensure both the smooth running of such a vast logistical operation and to provide our groups with information and all-around care.

The trip was split between a two day guided tour of the major areas and battles of the Western Front visiting locations around the Battle of the Somme, Arras and the Ypres Salient. As a first time guide at 25, it was incredible to see and speak to so many people in one location for the same purpose of commemoration. Hundreds of pilgrims would make their way to a site where the mood would often be lively and vibrant both on the coach and within the vast crowds walking the ground, yet when congregating at a location the atmosphere would be one of quiet, personal reflection.

The final day before departing witnessed all pilgrims form up to march through the Belgian town of Ypres where 1 in 4 British and Commonwealth soldiers who fought during the First World War were killed in defence of. 2200 standard bearers and wreath layers; now closer friends and comrades who had shared the tides of emotions often experienced on a battlefield tour stood side by side whilst their proud guides who became more and more attached to them waved them past and wished them well. As sixty coaches departed from the town, a sense of accomplishment and pride could be felt by everyone involved. The Great Pilgrimage of 2018 had achieved all it had set out to do and more.

Tom Saunders QGM

On 8 August 2018, I had the honour, privilege and pleasure to guide one of the many Leger Coaches in Flanders and on the Somme, as The Royal British Legion commemorated the 90th Anniversary of the Great Pilgrimage of 1928. Legion Standard Bearers and Wreath layers travelled from across the commonwealth to recreate the first pilgrimage of 1928. In many cases, 1928 was the first time widowed mothers and wives had a chance to visit their loved ones’ graves. What a sad occasion it must have been when 11000 pilgrims made the long journeys to France and Belgium.

We guided the GP90 clients on a battlefield tour of France and Belgium on a strict timetable selected specifically by the Royal British Legion in conjunction with Leger Tours. We visited iconic memorials like the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing on the Somme. It contains the names of over 72,000 soldiers whose remains were never recovered for formal burial. It’s the largest Commonwealth War Graves Commission memorial in the world and was designed by the famous architect Sir Edwin Lutyens. It stands tall and proud on the Thiepval Ridge and can be seen from across the wide-ranging battlefield.

We visited Tyne Cot Cemetery and Tyne Cot Memorial in Flanders. This cemetery is the largest Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in the world with almost 12000 burials and designed by eminent architect Sir Herbert Baker. On an arched stone wall at the rear of the cemetery stands one of four memorials to the missing within the Ypres Salient. The memorial contains the names of almost 34000 missing soldiers who died in Flanders. The cemetery and memorial stand overlooking the town of Ypres on what was the gentle ridge leading up to the nearby village of Passchendaele.

The final parade in Ypres was led by Northern Ireland man, Norman Espie as the legions National Standard Bearer. What a day we had in Ypres (Wipers). The GP90 Pilgrimage and parade were amazing. The colour, music, the splendour and the dignity of the parade was outstanding. The emotion of the occasion got to many visitors and participants and many a tear was shed during the beautiful service of remembrance. The Menin Gate itself was surrounded by over a thousand wreaths. The ghosts of Menin Gate no doubt looked on with great satisfaction and pride that their sacrifice in 1914 to 1918 was never forgotten. We will remember them.

The downside to this bias, of course, is that we miss the opportunity to garner a well-rounded appraisal of certain conflicts: the tactical approaches of Britain’s foes; the cultural impact war had on those countries; not to mention the personalities of the soldiers fighting for the other side, who are often demonised as cold, emotionless killers, when many – like our own men and women – were thrust into the field of combat against their will and better judgement.

The downside to this bias, of course, is that we miss the opportunity to garner a well-rounded appraisal of certain conflicts: the tactical approaches of Britain’s foes; the cultural impact war had on those countries; not to mention the personalities of the soldiers fighting for the other side, who are often demonised as cold, emotionless killers, when many – like our own men and women – were thrust into the field of combat against their will and better judgement.