How a place of detention, torture and murder became the home of the largest state sponsored forgery operation in the history of economic warfare.

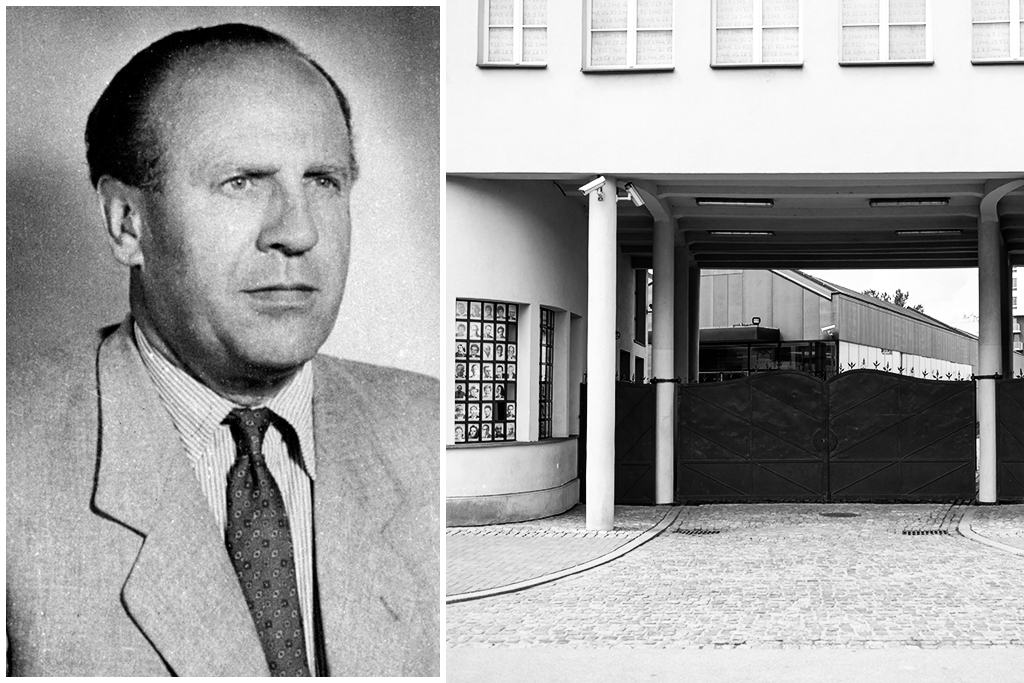

Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp was designed in early 1936 by SS Second-Lieutenant Bernhard Kuiper. The site was constructed in the shape of an isosceles triangle, with the apex at the rear of the camp and the two equal sides forming the camp boundary.

The base of the camp housed the gate house and administration building from which the whole camp could be observed. The wooden barracks were built on a semi-circle around the roll-call square. In 1937, Kuiper looked back on his work with pride, stating that Sachsenhausen was, ‘the most beautiful concentration camp in Germany’.

Andrzej Szczypiorski who survived the horrors of the camp disagreed. Years later, during a visit to the site of his detention and torture, he asked his fellow visitors, ‘do you remember our Sachsenhausen as an elegant camp?’.

The first prisoners incarcerated in the camp were those placed into ‘Protective Custody’ for either real or perceived offences against the state. By the end of 1936, the camp held 1,600 prisoners. Later, the camp held several other categories of prisoners including Jews, homosexuals, career criminals, asocial elements, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Soviet prisoners of war and Allied commandos/agents.

Prominent prisoners included Pastor Martin Niemoller, former Austrian Chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg, Georg Elser (responsible for planting the Burgerbraukeller bomb in November 1939), Herschel Grynzpan (responsible for assassinating German diplomat Ernst von Rath in Paris in November 1938), Yakov Dzhugshvilli (Stalin’s son) and three of the ‘Great Escapers’ Sydney Dowse, Johnnie Dodge and Jimmy James.

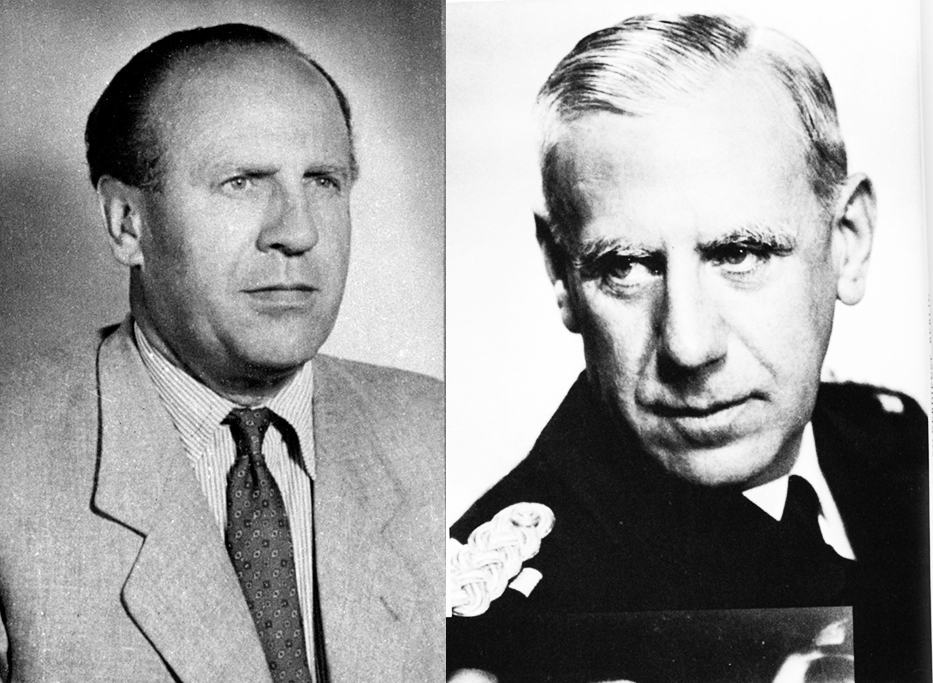

Apart from being a place of detention, torture and murder, Sachsenhausen became the home of Operation Bernhard, an audacious plot to destabilise the British economy by flooding it with fake currency. The operation was essentially a revival of Operation Andreas which ceased operations after it’s head SS Major Alfred Naujocks fell out of favour with the head of the Reich Security Services Reinhard Heydrich.

The new operation began in July 1942, and was headed by SS Major Bernhard Kruger who had arrested and subsequently incarcerated master forger Salomon Smolianoff in Mauthausen Concentration Camp three years earlier.

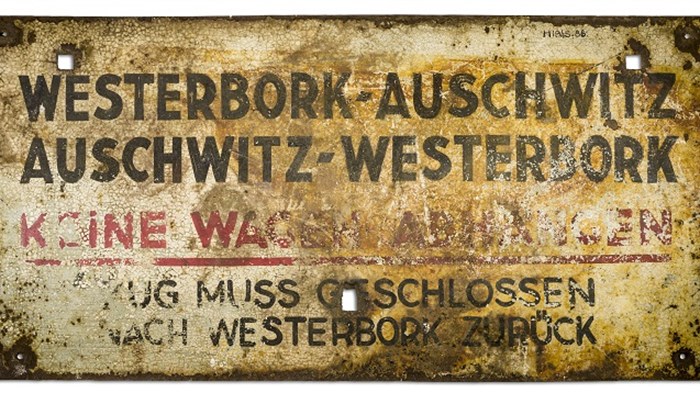

Operation Bernhard produced some 9,000,000 backdated notes in denominations of £5, £10, £20 and £50 to an estimated value of £134,000,000. For many years after the war, large numbers of fake notes remained in circulation, prompting the Bank of England to take drastic measures by withdrawing all notes larger than £5.

A new £5 note was produced in 1957. Seven years later, the £10 was reintroduced. However, it was not until 1970 that the £20 note was reintroduced. Incredibly, it took until 1981 for the £50 to be finally reintroduced. Such was the legacy of Operation Bernhard. Learn more about this fascinating subject on our Holocaust themed tour ‘The Story of Anne Frank and Oscar Schindler‘.

The second part of the Sachsenhausen blog will focus on the murder of Soviet prisoners of war, the liberation of the camp and its subsequent establishment as a Soviet ‘Special Camp’.