A battlefield tour can mean many different things to many different people, whether they’re on a journey of discovery, or something slightly more personal, what you take from an emotive experiences such as these tours will differ from person to person.

Catherine Miles recently published an article on her blog following her visit to Tyne Cot cemetery, on our All Quiet on the Western Front tour, in which she writes to her Great Uncle Sidney, who was sadly lost during one the Ypres salient of World War I . Catherine has kindly let us share with you on our blog.

In Search Of Great Uncle Sidney

It’s a beautiful summer Sunday afternoon in the late 1970s and I’m about 8 years old. I’m standing in the back garden of my Grandmother’s house in Dagenham. I can hear the whirring of hand pushed lawnmowers as neighbours cut their grass. My Great Uncle Frank is with me and has just handed me a bronze medallion, about 5 inches in diameter.

The medallion has a relief of Britannia with a lion at her feet on one side. There is also a rectangular box with an embossed inscription. I trace my fingers over the letters.

Private Sidney Greaves

“He was my brother. He was killed in the First World War”. I look up. Great Uncle Frank is looking intently at me with his piercing blue eyes. The same eyes of my Grandmother and Dad.

“He was very young. Never forget him, Cath. It’s important. Never forget.”

Dear Great Uncle Sidney (can I call you Sid?)

We never knew each other, and this may seem a bizarre letter to write. I’m your Great Niece – your little sister Winnie was my Grandmother. I’m writing this in Belgium, just outside Ypres, in an area I guess you came to know all too well. I’ve come to see where you and your mates fought.

There’s lots we don’t know about you but we’ve pieced together the bald facts of your story. You were born in 1898, the fourth of 7 surviving children of Mary and Herbert Greaves. You lived in extreme poverty in Birmingham. Your Dad was an electrical light switch maker, then a labourer and the family lived in two rooms at the back of a shared house in Bacchus Road. I’d imagine it was a tough existence, which only became tougher as you grew up.

By the outbreak of war in 1914 both of your parents had died, along with the step-father who your mother married after your father’s death. Your elder brother Wallace had died aged 8. There clearly wasn’t a lot of money around as your mother died in the workhouse hospital. Your sister Winnie had been placed in an orphanage, and from there she went into service from the age of 14. Your youngest brother Frank had been adopted by a caring local couple who set him on a very different path in life: education, a decent job, a family. Your two older brothers, William and Herbert, had both joined the Army and were fighting in France.

We know you enlisted in your local regiment, the Warwickshires, in Birmingham. We don’t know exactly when. Did you join up under age in the surge of patriotic enlistment in 1914? Or were you conscripted in 1916, when compulsory military service was controversially introduced? This looks more likely – you’d have been 18 and eligible for service. We know that after you joined the Warwickshire Regiment you were transferred into the 6th Battalion, Royal Wiltshire Regiment. This suggests you were conscripted in 1916 – it was after this point the Army started to re-allocate new soldiers from their local Regiments to Regiments they had no geographical connection to. This was prompted by the horrendous losses on the Somme, particularly amongst Kitchener’s Pals Battalions. The huge losses incurred by full frontal infantry attacks against machine guns meant that entire communities were decimated when their local Battalions suffered severe casualties.

So let’s assume you were conscripted in 1916 and sent out to France to join the Wiltshires a few months later. How did you feel? Scared? A sense of patriotic duty to do your bit? Excited for the adventure? Was it better than the alternative of fending for yourself in Birmingham living a hand to mouth existence?

It’s October 1988. I’m 17 and on a 6th form trip to the World War One battlefields. I’m standing at a windswept Tyne Cot Cemetery under leaden skies, looking at the rows and rows of neat white gravestones. I scan name after name of the missing on the stone tablets arcing round one side of the cemetery. I try to imagine what it was like for these lads, many my own age, to stand in those trenches then climb out over the top when the whistle went at dawn. And I can’t imagine the mix of fear, adrenalin and dread they must have felt.

I turn to join my classmates getting back on our coach as the rain starts to fall, raindrops streaking the names on the stone. What I don’t realise is the significance of one of those names.

The Wiltshire Regiment you joined had seen significant fighting during the War. The 6th Battalion was formed in 1915 from the rush of volunteers responding to Kitchener’s call to join the Army. It fought at the Battle of Loos and at the Somme, taking large numbers of casualties each time. By 1917 when you were likely to have joined it, the Battalion was in Belgium preparing to take part in the next great Battle.

So now we come to the part of your story where we know a little bit more. In summer 1917 the British Army launched a new offensive against the Germans around Ypres in northern Belgium, aiming to push them back from the salient and away from their strategically important ports. The offensive was led by General Plumer, one of the more innovative WW1 Generals, and started in 7th June 1917 with the detonation of 19 massive mines under the German lines at Messiness ridge. The simultaneous explosion of the mines was so loud it was heard in England. As General Plumer told the Press before the mines detonated ‘Gentlemen, we may not make history tomorrow, but we shall certainly change the geography’.

God knows how loud it was for you Sid – it must have sounded as if the world was exploding.

The mines were a success, and the British gained ground, with your Battalion (including you, most likely) fighting in the thick of the action. There was then a pause before what became the Third Battle of Ypres began. During this time there was unseasonably high rainfall, turning the clay-based ground into a water-logged quagmire. Trenches flooded, the shell holes that pockmarked the landscape filled with water and if you fell in you could drown in them.

This was the battlefield which you were to fight in. After three years of total war the landscape was totally desolate, without a building and barely a tree left standing. Ypres and the fields around it had repeatedly been fought over since 1914, the ground being gained and lost by either side. Trenches snaked through the very slight inclines of the land.

It was in one of these trenches that you were standing on the morning of 20th September 1917, waiting for the order to attack. You would have looked out onto a wasteland of mud, shattered tree stumps, jumbles of barbed wire, and the remains of unburied men and horses. Your Battalion was to take part in what became known as the Battle of Menin Road Ridge, attacking parallel to the ridge line.

You were exactly here, about to attack up this slope.

I can’t imagine what you were feeling, standing in that trench with your mates. What I do know is that, according to the Battalion War Diary, at 5.40am the whistle blew and you climbed out of that trench and attacked the German lines. With artillery shells falling around you, machine guns firing in front of you and snipers taking aim at you. The Battalion war diary records:

At zero hour 5.40a.m Battalion advanced to the attack under a heavy creeping barrage by our artillery. Left front Company met with little opposition except for continuous Machine Gun Fire from the direction of CEMETERY EMBANKMENT. The machine guns appear to be located beyond the objective line and to fire through the Barrage. The dugouts in the wood at about O 6 a 7.7. were dealt with 3 Germans being killed and 19 taken prisoner. As ‘D’ Coy on the right seemed to meet with considerable resistance Capt. Williams (O.C. ‘C’ Coy) ordered his right front Lewis Gun to open a brisk fire on the dugouts in front of that Company.

The Company reached its objective O 6a 75.65 – O 6a 3.7 within 37 minutes of Zero and flares were lit in response to aeroplane calls at Zero plus 42. The consolidation was covered by Lewis Guns and the Company Snipers who were busily engaged endeavouring to pick off Germans moving down the railway embankment and also keeping down enemy sniping on the immediate front – one platoon sniper remained isolated in a forward position from the morning of the 20th until relieved on the night 21/22. Left Support Company consolidated its section of the intermediate line, several casualties were caused by sniping. The ground was very wet and water logged in places but firesteps were formed with sandbags.

And then at some point on that day you were killed. You were 19 years old. Your body was never found or identified.

Ironically, the action you were killed in was one of the more successful ones of the war. However, the battle that followed was one of the most attritional and horrific the British Army has fought. It’s name – Passchendaele – continues to epitomise the suffering, sacrifice and for some, the futility of the First World War. In your battle the British Army advanced five miles at a cost of 100,000 men killed. 1 man for every 35 metres gained. 1 of them being you.

It’s May 2016 and I’m standing again at Tyne Cot Cemetery. It’s a peaceful and beautiful place where 12,000 British servicemen are buried, the largest British Cemetery in the world. This time, however, I know who I’m looking for. I walk round the stone curved wall containing the names of 33,000 servicemen who were killed but their bodies never found or identified. These names are only those of servicemen killed after August 1917 in the Ypres salient. The original intention was for all of the missing to be inscribed on the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres. But despite its enormous size it could only take 55,000 names – which wasn’t enough. So Tyne Cot was expanded to take the rest.

The curved wall is a striking feature but within it are two circular rotundas with carved panels containing more names. I walk towards the left hand one. It’s a peaceful tranquil space.

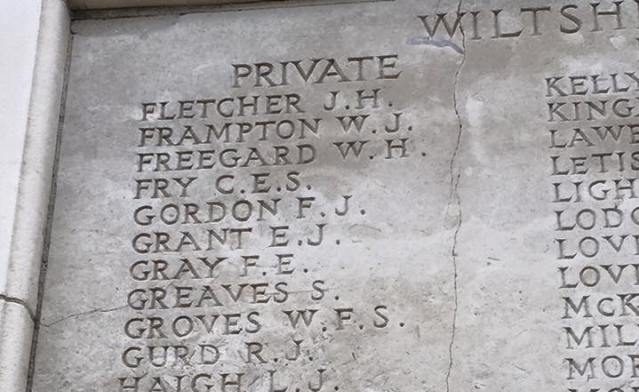

And there you are Sid, on panel 120. The Royal Wiltshire Regiment, Private Greaves, S.

I stare at the panel for a long time. I read the names around you. Were any of these lads were your particular mates? Which of the 5 NCOs listed was the toughest on you? Lieutenant Adam Shapland appears and he was killed on the same day as you, aged 22. Was he one of your officers?

I place a remembrance cross at the bottom of your tablet. On it I’ve listed the names of your brothers and sister. Will and Herbert survived the war, but Will was gassed and never really recovered. He died in 1944 from the effects of the gas nearly 30 years earlier. It must have been tough knowing they survived the war but their younger brother didn’t.

Your little sister Winnie married a sailor from East London (a cockney, news which may not please you) and had two sons. One of them is my Dad. I call him now and tell him I’m standing in front of your name. He’s glad we’ve found you.

And I think of my Great Uncle Frank, who made sure we knew about you and inspired me to come and find you.

So why do thousands of British people visit the WW1 battlefields every year to find the names or graves of relatives they never knew? There are 34 people on my trip and many are searching for relatives. One has come to see her Uncle, Harry Anderson of the Staffordshire Regiment. It turns out Harry is on a plaque just two down from you so I go to see him as well. Another lays a wreath in remembrance of the grandfather she never met at the mighty Thiepval Memorial which has the names of a further 72,000 missing from the Somme. The losses of the First World War were so great they touched every family in the country. There were over 730,000 British servicemen killed – sons, fathers, brothers, uncles and friends.

I came to Tyne Cot because I wanted to honour your memory and pay tribute to the incredible bravery and sacrifice of you and your generation. I’m acutely aware and grateful that I have a life of comfort and opportunity which would have been unthinkable to you. I wanted to keep my promise to your brother Frank to remember you.

And I wanted to let you know that your family loved you, and cared enough to make sure that your great nieces and great nephews knew your story.

You have never been forgotten, Sid. For me, it’s so important that all of us who came after you remember you and remain eternally grateful that we have never found ourselves on the front line, being ordered to climb out of the trench.

With love from your great niece

Catherine