The abandonment of Soviet prisoners by Stalin and the subsequent re-establishment of the camp as a special Gulag.

The first Soviet prisoners arrived at Sachsenhausen in August 1941. By the end of the year, more than 11,000 of these living skeletons were being held in the camp in appalling conditions. Impossible work conditions, meagre rations and mass executions steadily reduced their numbers.

The most common method of execution was by shooting in the so-called ‘neck shot facility’ located close to the camp crematoria. Here, an estimated 10,000 Soviet prisoners were executed over a ten week period during late 1941. Total estimates of Soviet prisoners murdered in the camp between 1941-45 vary between 11,000 – 18,000.

None of this mattered to Stalin, whose attitude towards captured troops was underlined in his statement that, ‘There are no Soviet prisoners of war. The Soviet soldier fights on until death. If he chooses to become a prisoner, he is automatically excluded from the Russian community’. This attitude even extended to his own son, Lieutenant Yakov Dzhugshvili, following his capture during the Battle of Smolensk on 16 July 1941. Soon after, Stalin ensured that the wife of this ‘Traitor to the Motherland’ was not spared the state’s wrath. Yakov’s wife Julia was subsequently arrested, separated from her three year old daughter and imprisoned in the Gulag for two years.

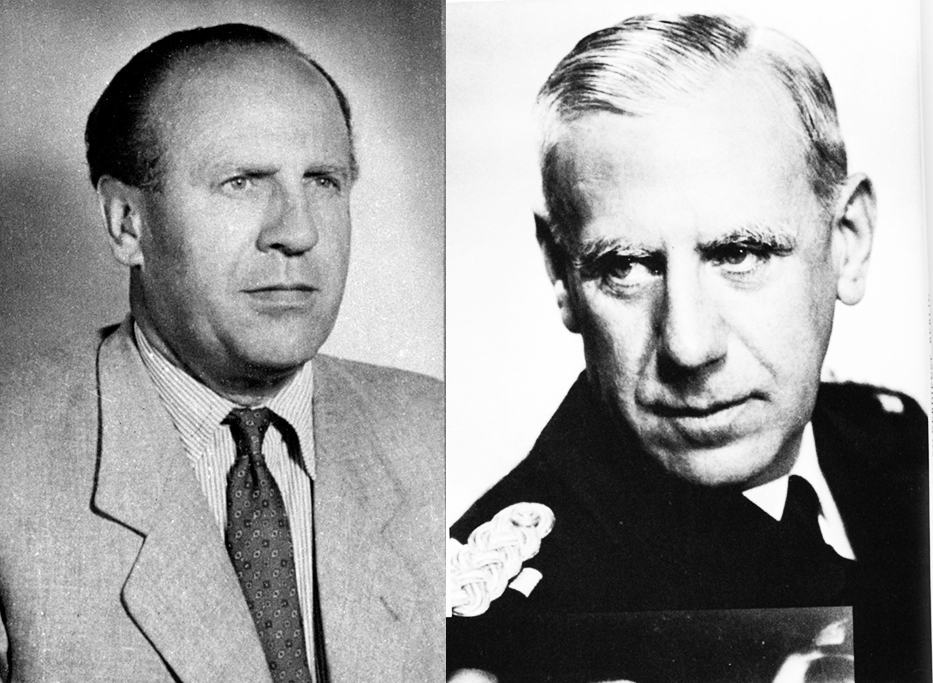

Following the German disaster at Stalingrad in February 1943, Field Marshal Friedrich von Paulus was taken prisoner. Soon after, the Germans suggested a prisoner swap, their senior officer for Stalin’s son. Inevitably, Stalin turned the offer down, saying that, ‘I will not trade a Marshal for a Lieutenant’. On 14 April 1943, Yakov was shot and killed. Contemporary reports indicated that he was shot whilst approaching the camp’s prohibited ‘Neutral Zone’ which bordered the electric fence. More recent investigations point to him being killed for refusing to obey an order to return to his barracks. In March 1945, Stalin talked with Marshal Zhukov about his son, whom he believed was still alive and being kept as a hostage. His hard heart began to soften a little towards a son who had once been dismissed by him as ‘a mere cobbler’. When the death of Yakov was later confirmed, Stalin rehabilitated him posthumously in the knowledge that he had died honourably.

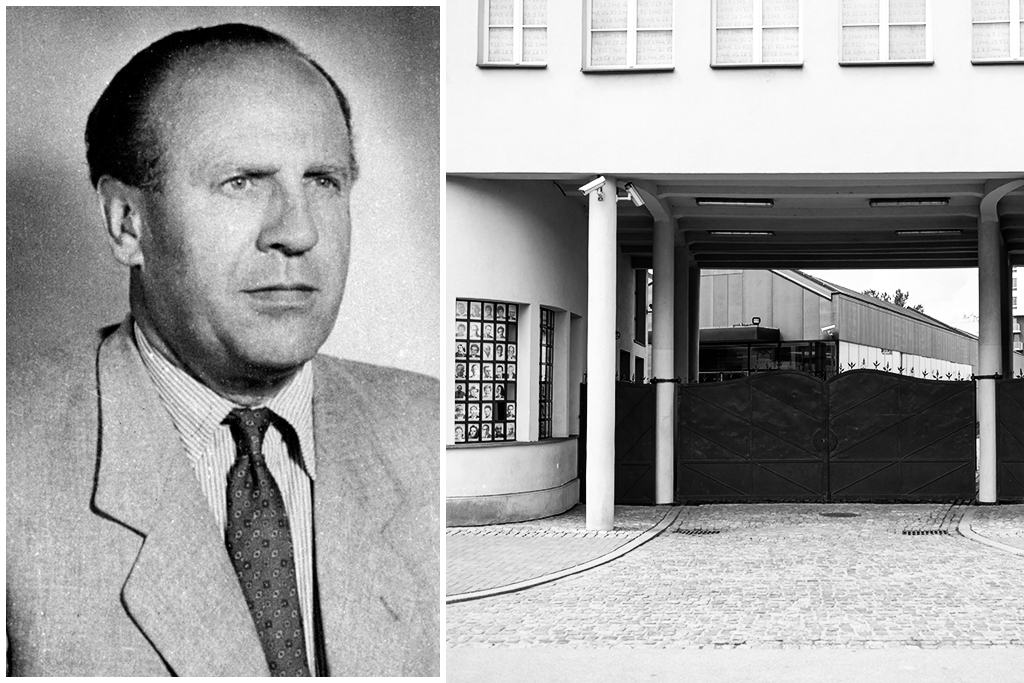

The liberation of Sachsenhausen on 22 April 1945 came too late for Stalin’s son. Neither did liberation bring comfort to thousands of Soviet prisoners who had effectively been abandoned by the state. For them, there was no hope of rehabilitation, just interrogation by Smersh (Soviet Military Counter Intelligence). Stalin’s assertion that there were no Soviet prisoners of war, just so-called ‘Traitors to the Motherland’ condemned them to imprisonment and hard labour in the Siberian Gulags. Some Russian prisoners were held in Sachsenhausen (renamed by the Soviet authorities in August 1945 as Special Camp No.7).

The arbitrary enmity of the Soviet organs of repression resulted in the convictions (after interrogation and torture) of alleged Nazi collaborators and soldiers who had contracted venereal disease in Germany. By 1946, the camp held approximately 16,000 German and ex-Soviet citizens (including 2000 women prisoners). In 1948, the camp was redesignated as Special Camp no.1. That year, some 5000 German prisoners were granted an amnesty and freed. Another 5,500 German prisoners were freed in early 1950. More German prisoners were freed shortly before the camp was shut down in the Spring of that year. The few remaining Russian prisoners were transferred to the Gulags on Soviet soil.

For those so-called ‘Traitors to the Motherland’ who somehow survived their harsh treatment and subsequent cold-shouldering by the state, their ordeal was not over. Their rehabilitation did not finally come until after the fall of Communism in 1989. We still tend to associate cruelty and barbarity almost exclusively with Nazism, yet Stalin’s state was also brutal and unforgiving. Learn more about Soviet Special Camp No.1/No.7 on Leger’s ‘The Holocaust Remembered‘ tour.

Read part one of David’s Sachsenhausen blog, here.